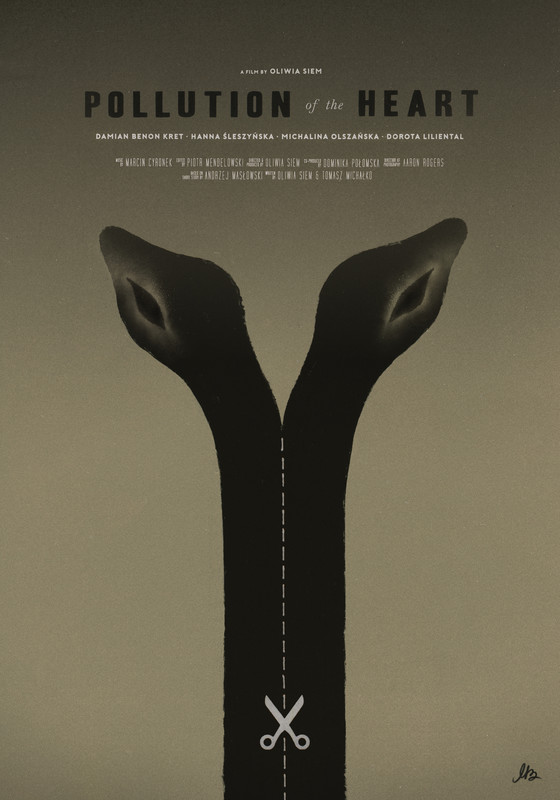

Pollution of the Heart is a suspenseful film that mixes archaic, claustrophobic interior spaces with the overwhelming suffocation (and perhaps horrific nature) of the love between parent and child. The film’s protagonist David is not quite an average young man. In our first glimpse of him, he’s playing dead in a coffin in a mortuary storage room, while his girlfriend takes pictures of his reposed body. This isn’t the last time we see him play dead, but the fact that he is being photographed does immediately introduce the idea of the double, of David’s mirror image, a thread that runs throughout the film. While David is supposed to meet his girlfriend later that evening, we learn that he must first see his long-suffering, manipulative mother, who relies on him for groceries and doesn’t seem to leave her sumptuous, stuffy apartment. While David attempts to go out, his mother tries to envelop him in the world of her past. Over the course of an evening, she seems to fall apart mentally, and at first it seems to be a ploy to separate David from his girlfriend. However, as secrets about David’s and his mother’s pasts are revealed, the film vacillates between two premises: is she slipping into insanity, or is there something more sinister afoot?

Pollution of the Heart is a suspenseful film that mixes archaic, claustrophobic interior spaces with the overwhelming suffocation (and perhaps horrific nature) of the love between parent and child. The film’s protagonist David is not quite an average young man. In our first glimpse of him, he’s playing dead in a coffin in a mortuary storage room, while his girlfriend takes pictures of his reposed body. This isn’t the last time we see him play dead, but the fact that he is being photographed does immediately introduce the idea of the double, of David’s mirror image, a thread that runs throughout the film. While David is supposed to meet his girlfriend later that evening, we learn that he must first see his long-suffering, manipulative mother, who relies on him for groceries and doesn’t seem to leave her sumptuous, stuffy apartment. While David attempts to go out, his mother tries to envelop him in the world of her past. Over the course of an evening, she seems to fall apart mentally, and at first it seems to be a ploy to separate David from his girlfriend. However, as secrets about David’s and his mother’s pasts are revealed, the film vacillates between two premises: is she slipping into insanity, or is there something more sinister afoot?

Drawing from Roman Polanski and David Lynch, the film’s most impressive features are its gorgeous, highly saturated color palate and its oppressively ornate mise-en-scène. The film has a painterly quality, if that painting was eerily garish and slightly unnerving. Far from being distracting or overly decorative, the setting mirrors the emotional interior of the mother herself. Once considered opulent and beautiful, the apartment has fallen into disrepair, and is dusty and seedy. The sophisticated camerawork also highlights the aged beauty of the film’s milieu, and it also helps create intimacy with our protagonist. As the camera follows David with increasing intimacy throughout the film, showing him first being photographed, then in a series of close ups and mirrored shots, it allows to suspect that David may not be a singular entity.

Hanna Sleszynska, who plays the mother, is particularly striking in her role as the manipulative, yet legitimately suffering mother. Her tension, her inability to separate dream from reality, and her shrill, clingy love illustrate the sufferings of woman torn between love for her child(ren) and fear of her own death. Damian Kret, who plays David, is also good as the young man obsessed with death, in what first appears to a trivial and then later a more legitimate way.

While the film’s closure arrives quickly and is a bit too obvious, the film nevertheless manages to maintain its eerie tension. Whether showing a baroque, deteriorating apartment or the banality of modern public transportation, the film contains a sinister undercurrent and maintains the idea that something profoundly not right is lurking behind every corner, or more terrifyingly, in the bodies of our most treasured loved ones.