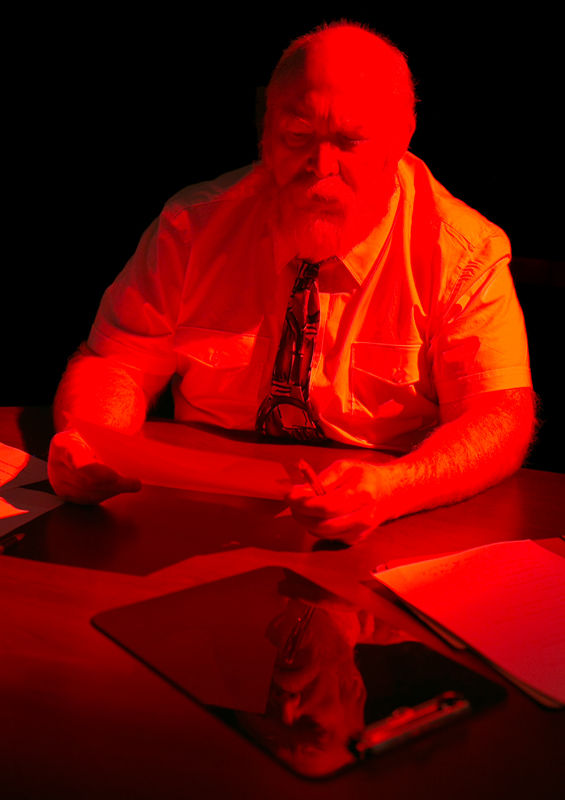

In the loose narrative of the short film Alchemy, a man suffers through what appears to be the world’s least pleasant job application and interview, which ends up transforming him into a being that can exist within two worlds simultaneously. In its initial sequence, a man is led into a banal conference room and told to “fill out the application in its entirety.” However, as he begins to fill out the forms (which appear numerous, even from the beginning), time elongates and the room seems to turn against him. The door locks, the lights go out, and his forms catch on fire. Alone, in the dark, he begins to be interviewed by a voice from above and suffer from visual and auditory hallucinations.

In the loose narrative of the short film Alchemy, a man suffers through what appears to be the world’s least pleasant job application and interview, which ends up transforming him into a being that can exist within two worlds simultaneously. In its initial sequence, a man is led into a banal conference room and told to “fill out the application in its entirety.” However, as he begins to fill out the forms (which appear numerous, even from the beginning), time elongates and the room seems to turn against him. The door locks, the lights go out, and his forms catch on fire. Alone, in the dark, he begins to be interviewed by a voice from above and suffer from visual and auditory hallucinations.

The film’s greatest strength is its ability to slip between the seeming banality of modern life and the myths of humanity’s pre-Enlightenment past. At first, the film only subtly connects the film’s corporate setting to the elemental symbols so prominent in the concept of alchemy; lights and colors change, papers catch on fire, snow covers the window and leaves the interviewee sightless to the outside world. By making these slow but sure connections, however, the film ruminates on the fine line between the prosaic and magical that undergirds everyday life. The monotonous dim of fluorescent overhead lights and the red glow of an average exit sign transform into more unearthly and disturbing sensory experiences. Everyday objects of modern capitalism, such as paper or a window, are rapidly changed without warning.

The film’s camera work mimics these elemental experiences. At first, the still camera references the modern setting, its immobility mimicking security cameras or the disembodied presence of a CEO portrait. However, as the film’s tensions rise and the protagonist’s sanity is questioned, the camera becomes a saturnalia of movement, highlighting the unreal experience and the terror (as opposed to the wonder) of transformative magic. As such, the film seems to reference older modes of experimental filmmakers, such as Antonin Artaud or Kenneth Anger, who emphasized the mythic body experience of cinema. While the film may not quite reach the rawness of those early experimenters, it nevertheless takes risks by shedding contemporary verisimilitude for past psychedelics.

And, while sometimes the protagonist’s actions appear extreme or overwrought, the bacchanalia makes sense when the interviewee aces the interview and the job is finally revealed. The film’s end deftly connects an ordinary (perhaps even infantile) present to an older, deeper mythology that lurks beneath the everyday world.