While the shot composition in Richard Schertzer’s “Nature” is finely handled, as well as contemplative in rhythm and gaze, and the music nobly intentioned to resound with the serenity of the natural landscape being depicted, the cinematography itself unfortunately fails to provide a distinctive texture or captivating visual framework for the viewer. Instead, the imagery looks stark and barren, which is one thing if that suits the environment under inspection (such as the blistering coldness in the cinematography of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “The Revenant”), but here the beauty and the solemn abandon of the swaying trees appears flushed of its color, with a sun that should be vibrant and prismatic rather blurred and suppressed in the background of the shots. In the end, “Nature” delivers a watchful eye for the outdoors, but one that does not yet have the aesthetic, or the proper sound design, to back it up.

While the shot composition in Richard Schertzer’s “Nature” is finely handled, as well as contemplative in rhythm and gaze, and the music nobly intentioned to resound with the serenity of the natural landscape being depicted, the cinematography itself unfortunately fails to provide a distinctive texture or captivating visual framework for the viewer. Instead, the imagery looks stark and barren, which is one thing if that suits the environment under inspection (such as the blistering coldness in the cinematography of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “The Revenant”), but here the beauty and the solemn abandon of the swaying trees appears flushed of its color, with a sun that should be vibrant and prismatic rather blurred and suppressed in the background of the shots. In the end, “Nature” delivers a watchful eye for the outdoors, but one that does not yet have the aesthetic, or the proper sound design, to back it up.

Page 3 of 10

Daniels Joffe’s “En Garde!” is a visually accomplished, snappily edited portrait of a unique experience, one that follows a young boy’s coming of age and growing sense of self in the often overlooked world of competitive fencing.

Daniels Joffe’s “En Garde!” is a visually accomplished, snappily edited portrait of a unique experience, one that follows a young boy’s coming of age and growing sense of self in the often overlooked world of competitive fencing.

The athletic scenes here are well executed, utilizing an array of camera angles and perspectives, along with tense sound design and a frenetic, high-energy editing style that capture the heat of the moment in fencing matches.

Where the film falters, then, is mostly in its music and dialogue quality, for the two elements often interact in a way that is melodramatic and thus more on-the-nose and ineffective compared to the visual style. However, that being said, the cinematography, performances, and editing are enough to prove this film a worthy opponent, and one with a singular focus.

Sara Eustaquio’s “Slumberous” establishes a sense of dread and an oppressive nighttime atmosphere through a droning sound design that renders both the protagonist’s house and the outdoors around it alien and unnerving.

While the shot composition and acting are also compelling enough to sustain the narrative momentum and ominous mood , the greatest weakness of Eustaquio’s film perhaps comes from the script itself. The main character’s choice to murder her hamster by the end seems unmotivated and unearned; while the house is certainly producing a horrific effect through sheer uneasiness, it makes little sense that she would decide to go for her pet first and foremost, especially since the grating squeaks of the hamster wheel are only briefly revealed to us as viewers. Everything else, in fact, appears more brutalizing to the senses than the hamster wheel, so it would have been more relevant to the narrative progression to have the protagonist burn down her house, for instance.

While the shot composition and acting are also compelling enough to sustain the narrative momentum and ominous mood , the greatest weakness of Eustaquio’s film perhaps comes from the script itself. The main character’s choice to murder her hamster by the end seems unmotivated and unearned; while the house is certainly producing a horrific effect through sheer uneasiness, it makes little sense that she would decide to go for her pet first and foremost, especially since the grating squeaks of the hamster wheel are only briefly revealed to us as viewers. Everything else, in fact, appears more brutalizing to the senses than the hamster wheel, so it would have been more relevant to the narrative progression to have the protagonist burn down her house, for instance.

Overall, “Slumberous” is an effective exercise in horror aesthetic, but unfortunately it lacks a cohesive script to finely shape its trajectory.

Michael Salmon’s “Goodbye Mondays” follows an increasingly dangerous situation faced by a maid named Lucy (Gillian Saker). After a frustrating encounter with her snobbish employer (who is currently sleeping with an unseen man in her bedroom), Lucy engages in a heated phone call downstairs with the woman’s real husband, who offers her a large sum of money to kill both his wife and the man she is having an affair with.

An escalation of events is developed with great strategy from the start, as we are flooded with brightly white, porcelain lighting and mise-en-scene that is flushed, almost sanitized, in its color palette. Contrast this with a brief intervention of darkly saturated, reddish lighting from within the woman’s bedroom and a nice foreshadowing of violence is established.

An escalation of events is developed with great strategy from the start, as we are flooded with brightly white, porcelain lighting and mise-en-scene that is flushed, almost sanitized, in its color palette. Contrast this with a brief intervention of darkly saturated, reddish lighting from within the woman’s bedroom and a nice foreshadowing of violence is established.

Saker gives a stoic performance that cracks with fragility, paying due attention to all facets of her character: the newly-hired innocence, the growing desperation, and the festering vengefulness. The voice of Adrian Schiller as the woman’s husband commands both Saker’s character and the dramatic action itself, delivering a smooth-talking, persuasive devil of a presence. He, too, has moments of fragility and rage, which is probably why he and Saker create a striking dynamic together, even with the former being unseen for the duration of the film.

By the final moments of “Goodbye Mondays,” we are left with the callousness of such an extreme ultimatum, along with the implied consequences that Saker’s character will face after having carried out someone else’s criminal intent. While her motivations perhaps could have been established with more tactfulness and deliberation, especially considering the actions she eventually performs, the film’s cinematographic and performative strengths nevertheless propel this twisted series of events in a captivating way.

Like any traditional Drama/ Romance/ Dance genre film, STAND SURE (Mulvany and Wild, 2017) leans on the idea that effort and hard work can overcome any obstacles. The movie’s story begins with its heroine, Danica (also the name of the dancer that plays her), stuck in a walking boot because she’s ripped her Achilles tendon. Dejected, she tells her friend/coach/and possible love interest Connor that she couldn’t possibly dance in an upcoming event. He, however, thinks that she has the strength to try, and begins coaching her for the competition.

We then are given a series of training montages that are the backbone of the sports film—from Rocky to Dirty Dancing to Ali—and the way to shorten time exponentially. What makes STAND SURE a little more unusual is the kind of competition itself: Highland dancing . Ever since the emergence of “Lord of the Dance,” which thrust Irish dancing into mainstream culture, different modes of Celtic have a taken on a campy, Vegas feel that is entirely absent here. In the film, highland dancing is a series sport, complete with rigorous training, skill, and pain. We are given this image metaphorically through Danica’s constant ice baths—which consistently has represented the toll on the body that competitive athleticism brings.

. Ever since the emergence of “Lord of the Dance,” which thrust Irish dancing into mainstream culture, different modes of Celtic have a taken on a campy, Vegas feel that is entirely absent here. In the film, highland dancing is a series sport, complete with rigorous training, skill, and pain. We are given this image metaphorically through Danica’s constant ice baths—which consistently has represented the toll on the body that competitive athleticism brings.

The film is well-paced and fast-moving, and the training montage aptly conveys Danica’s physical struggle to overcome her injury and compete. In addition, the two leads do have a certain amount of chemistry. Danica Wild—likely more of a dancer than an actor, plays the lead very competently in the role of a struggling athlete. However, while the film definitely has a certain good-natured charm, it does little to distinguish itself from other films of the same genre. As a vehicle that shows the strength and beauty of Highland dancing, though, it does well to introduce globally the intense athleticism and seriousness of the sport.

There are a lot of great films getting drunk, high, or otherwise loaded and pursuing the idea of a drunken point of view. It’s not so much the drunkenness itself but that intimate connection between camera and perspective. In Ken Russell’s Altered States, scientists even imagine inebriation as the entry into a new reality, in which drugs become the cinematic catalyst for playing with light, sound, angle, color, and perspective, all in ways that defy typical perception.

Andrea Baglio’s NATURAE (2017) is a short made with that tradition in mind. In the film, a young man–caught in the throes of a drunken haze—staggers into the wilderness (or, at least, a very large garden). There, the camera seems to shift from watching the young man to adopting his point of view. This is where the photography becomes beautiful, almost sentient. As we jump back and forth between the view of our drunken protagonist and his POV, we see nature as an oversized expression of the sublime. Flowers grow to oversized behemoths; winter trees are shrouded in mystery and secrets of the world. Nature is by turn beautiful, horrific, gross, overwhelming, and sensual.

Andrea Baglio’s NATURAE (2017) is a short made with that tradition in mind. In the film, a young man–caught in the throes of a drunken haze—staggers into the wilderness (or, at least, a very large garden). There, the camera seems to shift from watching the young man to adopting his point of view. This is where the photography becomes beautiful, almost sentient. As we jump back and forth between the view of our drunken protagonist and his POV, we see nature as an oversized expression of the sublime. Flowers grow to oversized behemoths; winter trees are shrouded in mystery and secrets of the world. Nature is by turn beautiful, horrific, gross, overwhelming, and sensual.

NATURAE gestures toward Antonin Artaud’s experimental theater and art spaces, toward the happenings of the 1960s in which the sensory experience mattered far more than the narrative representation. While it doesn’t necessarily completely reach that sensory overload, it nonetheless brings a fresh sense of experimentalism into a contemporary film, which is so often dominated by strong storylines. NATURAE celebrates the pure image, which really can only work if the photography is strong, which it is.

Being in a teenaged girls head is a little bit like being in a lunatic asylum. Not in the sense that teenaged girls are crazy, although that may or may not be the case, but that they are always told that they are crazy and that “sanity” is right around the corner if they just try hard enough. Unfortunately for them, however, those who are driving them crazy are also telling them to be better. Girls are sold an amazing amount of mixed messages: they are beautiful just as they are but should buy make-up, creams, and serums to look better; that they should be confident but not too confident; sexy but not too sexy; that they are beautiful, that they are ugly. With all of these competing ideas scurrying around in a rapidly growing, hormonal brain, it’s no wonder that girls often turn to anorexia, bulimia, self-harm, and drugs.

HAPPY DOLLS attempt to get inside the mental space of one of those teenaged girls. A teenaged girl, spurred by a fleeting moment of self-confidence, ask out a boy on whom she has a crush. He, however, instead crushes her dreams and expectations by mocking her with another friend. Disappointed, she wanders off, but the bullying has obviously gotten under her skin. She transfers these feelings from other onto herself in violent and abusive ways. In this case, HAPPY DOLLS speaks to ways that girls believe criticism and turn in inward, usually with vicious and detrimental results.

HAPPY DOLLS attempt to get inside the mental space of one of those teenaged girls. A teenaged girl, spurred by a fleeting moment of self-confidence, ask out a boy on whom she has a crush. He, however, instead crushes her dreams and expectations by mocking her with another friend. Disappointed, she wanders off, but the bullying has obviously gotten under her skin. She transfers these feelings from other onto herself in violent and abusive ways. In this case, HAPPY DOLLS speaks to ways that girls believe criticism and turn in inward, usually with vicious and detrimental results.

While HAPPY DOLLS does a good job in getting its point across in a very short period of time, its imagination is nonetheless bigger than its production values. The film struggles with less experienced actors and little budget, filming in a naturalistic style that doesn’t really connect to the gravity of its subject. However, what we do see here is Beltran’s strong point of view and willingness to experiment, which is what young filmmakers need to grow.

Maya Jasmin’s seemingly semi-autobiographical ROOFTOPS OF MY CITY explores how people come to find a city home, especially in the transient, cosmopolitan, immigrant-rich New York. The story follows two characters, a young Swiss burgeoning actor named Oliver, and a German up-and-coming DJ named Lena, whose diverse origins leave her struggling to contact with other. The two live one rooftop apart, and even have some conversations but only begin to really know each other after Oliver overhears Lena speaking German and recognizes as linguistic kin. In getting to know each other, the two discover that they have that ex-patriot bond that seems to connect so many émigrés in foreign lands. They miss Becks beer and speaking German. They both feel like their backgrounds are amorphous and hard to describe. Lena feels German, Japanese, and Polish simultaneously, while Oliver feels not-quite-German at German bars.

There’s a lot to ROOFTOPS OF MY CITY that is quite  refreshing. Oliver and Lena have good chemistry that is not romantic but evokes the odd compatriotism that émigrés share. The photography evokes everything that is simultaneously great and problematic about Brooklyn. The pastel shades and dusky light conveys the strange, urban beauty and lonely strangeness that characterizes Brooklyn, a place in which you can be always and never alone simultaneously. Moreover, the actors are sweet, credible, and awkward enough to show how strange a new, actively pursued friendship can be. The director plays Lena, who is clearly a version of herself, while Terrence Schweizer has a very credible performance as a burgeoning actor.

refreshing. Oliver and Lena have good chemistry that is not romantic but evokes the odd compatriotism that émigrés share. The photography evokes everything that is simultaneously great and problematic about Brooklyn. The pastel shades and dusky light conveys the strange, urban beauty and lonely strangeness that characterizes Brooklyn, a place in which you can be always and never alone simultaneously. Moreover, the actors are sweet, credible, and awkward enough to show how strange a new, actively pursued friendship can be. The director plays Lena, who is clearly a version of herself, while Terrence Schweizer has a very credible performance as a burgeoning actor.

The dialog can be a bit awkward and forced, however, and the revelations that the two have are fairly normal for anyone of complex backgrounds. It seems that this is older, well-worn territory for young people who have grown up in this globalized world. The characters are charming, though, which makes up for the facileness of their conclusions. ROOFTOPS evokes that first move after college and struggle to make our place in a brave, new, world. We really root for them to succeed in their new homes, and, in such a character-driven movie, and may be the real thing that recommends it.

In Mehmet Ger’s THE CONTRACT, it’s crucial to convey meaning outside of the dialog. Of course, film is clearly a visual medium, but we often forget the significance of sound. Sound creates three-dimensional space, helps characters move, emphasizes mood, and uses dialog to create meaning. In a film like THE CONTRACT, in which dialog is absent, the key is to be able to convey both mood and meaning without talking.

However, what is the most fun of The Contract is how it uses sound to play with depth. In the short piece, an unnamed man enters into a non-descript high-rise for an interview. The vast majority of the film is the figure traveling through space and the auditory signals that go along with it. He opens doors, traverses long highways, and otherwise makes space real in this echoing, almost empty building. As he is led through the labyrinthine hallways, the clicking of his female guide’s pointy stilettos dominates the soundscape.

However, what is the most fun of The Contract is how it uses sound to play with depth. In the short piece, an unnamed man enters into a non-descript high-rise for an interview. The vast majority of the film is the figure traveling through space and the auditory signals that go along with it. He opens doors, traverses long highways, and otherwise makes space real in this echoing, almost empty building. As he is led through the labyrinthine hallways, the clicking of his female guide’s pointy stilettos dominates the soundscape.

The juxtaposition between silence and background noise creates an ominous mood that is matched by the austere, empty setting and harsh, corporate lighting. Like many films that use a blue filter, the film presents a cool, harsh landscape that seems infertile and sterile, which fits in excellently with the film’s final images.

However, even given the film’s limited scope, it seems to have challenges conveying it’s meaning. The film leaves several questions unanswered, including what is the larger background of the world in which this particular event takes place? The film’s combination of knowing glances and blank stares create an eerie sense of a world without human desires, needs, or wants. However, the film leaves with a strong mood—but little sense of the circumstances that make this world possible.

That being said, the film is definitely a fun experiment in sound at a time in which sound has become second to the dominance of the image. Much like its earlier predecessors of the early sound era that attempted to understand the role of diegetic sound in the moving images, The Contract emphasizes the three-dimensionality of cinematic space, even though its characters are fundamentally two dimensional.

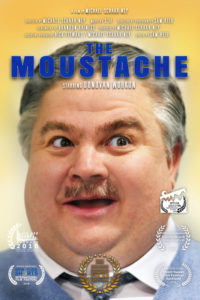

Some of the best comedy is built on absurdity. In Kubrick’s DR. STRANGELOVE, the heightened symbolism that connects sex, dominance, and war provides a fantastic spoof on hyper-masculine American military culture. Meanwhile, in films like Gilliam’s BRAZIL, banal disinterest in catastrophe, terrorism, and torture speaks to our ability to slide quite easily into authoritarianism. This is not to say that Michael Schaar-Ney’s THE MOUSTACHE rises to the level of BRAZIL or STRANGELOVE, but it nonetheless plays on our culture’s most ridiculously tendencies, in this case, the notion of fashion and image as self-improvement.

In the film’s narrative, a portly, nebbish office worker named Mike decides on the fly to grow a mustache. While he hopes it may make him appear more charming (especially to his neighbor), he is surprised by the radical changes that a mere mustache made in his life. His neighbor notices him for the first time, he gets a promotion at work, and his life starts to turn around. Of course, as it begins to pay off for him big time, he also begins to get carried away by the glory of his mustache.

In the film’s narrative, a portly, nebbish office worker named Mike decides on the fly to grow a mustache. While he hopes it may make him appear more charming (especially to his neighbor), he is surprised by the radical changes that a mere mustache made in his life. His neighbor notices him for the first time, he gets a promotion at work, and his life starts to turn around. Of course, as it begins to pay off for him big time, he also begins to get carried away by the glory of his mustache.

Like most good comedy, the film’s humor comes from its pacing, reiterated. Mike appears somewhere, and people at first flustered then intrigued and then entranced. And, because it’s a comedy, the banal workspaces, bars, and apartments serve only to highlight the absurdity of Mike’s newfound celebrity.

While all this doesn’t raise THE MOUSTACHE to a comedic masterpiece, it does show an emerging filmmaker who understands what makes absurdity great and can accomplish this in a small piece.

© 2025 Ouchy Film Awards

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑